Licensed To Kill: Interview with Arthur Dong

Cineaste

December 1997, vol. XXIII, no. 2, pages 20-23

by Thomas Doherty

In 1955 when a black teenager named Emmet Till was murdered by two white men in Mississippi Delta, William Faulkner reflected upon the circumstances under which “two adults, armed, in the dark, kidnap a fourteen-year-old boy and take him away to frighten him. Instead of which, the fourteen-year-old by not only refused to be frightened, but, unarmed, alone, in the dark, so frightens the two armed adults that they must destroy him.” “What,” Faulkner wondered, “are we Mississippians so afraid of?”

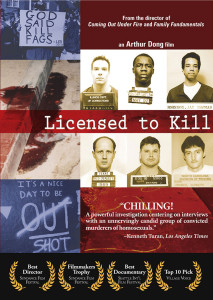

That kind of fear animates Licensed To Kill, Arthur Dong’s documentary investigation into the minds — confused, twisted, and quite sane — of seven killers of gay men. Inspired by an attack Dong fell victim to at the hands of four teenagers in 1977, the director seeks to discover what propels a pathology, “to actually meet the men whose contempt for homosexuals leads them to kill people like me.” His exploration crosses personal motives and popular culture, individual gripes with a national ethos that nourishes a hate that can prove fatal.

Weaving together the crimes and the comments of the six killers, Licensed To Kill is skillfully edited, and consistently riveting. No less than a fancy prose style, you can always count on a murderer for magnetic screen presence. With the exception of the official police interrogation of Raymond Childs, whose confession to robbery and murder slips in and out of the narrative as a leitmotif, Dong conducted all of the interviews himself. Although he remains off camera and his voice is heard only sparingly, his expository comments makes him a controlling and intense presence during the encounters between the haters and the hated.

In one sense, Dong’s impulse is a classic example of liberal sympathy: an imaginative effort to explore the dark places of alien souls in the hope that by understanding what makes them tick, they (or the time bombs still ticking) can be spotted and defused. Seemingly grateful for the break from prison monotony, the murderers try to be helpful. “The rage came out of nowhere,” says William Cross, a handsome hardbody who bares his tattoos along with his backstory. A couple attribute their rabid hatred of gay men to child molestation, others to fundamentalist Christianity. Another seems merely deranged in an uncomplicated way. After chugging down a fifth of whisky while watching Clint Eastwood’s Licensed To Kill, Army sergeant Kenneth Jr. French walked into a restaurant and opened fire with a shotgun because he “needed to voice my opinion about” Clinton’s decision to allow gays in the military. The perpetrator of the deadliest and most unfocused assault, French is also the killer who shows the most remorse in a courtroom statement at trial. With these guys, though, the really sincere sympathy is reserved for themselves because they wasted their own lives, not because they wasted another’s. “It was a bad night for me anyways,” Texas death row inmate Donald Aldrich says of the evening he and two accomplices pumped nine gunshots into Nicholas West.

As a genre, the documentary portrait of the killer haunts the 1990s the way the film noir shadowed the 1940s. In innumerable cable biopics and independent features, killers single and serial conjure an instant storyboard in models to satisfy all tastes: pantheon overachievers (the bread and butter of A&E’s Biography series), teenage apprentices (Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky’s Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills, and distaff oddities, The Elaine Woronos Story). Like the bulging true-crime shelves of bookstores, the documentary cycle favors remorseless murderers, not quirky and deranged headcases like Norman Bates but cold and rational professionals like Hannibal Lecter, socio- not psycho-paths. The gay-bashers in Licensed To Kill are not serial killers, but not for want of trying; they are too stupid and spontaneous to hunt with cunning and cover their tracks.

In the esthetic style that defines the modern ‘forensic noir,’ raw visual conventions favor police mug shots, crime scene photos, local news reports, amateur video, and talking-head interviews, a low tech ambiance that makes for drama at a high pitch. The music track is synthetic and grim, a low-level undertone operating on the edge of consciousness. The stark mise-en-scene is ready-made and government issued, a mobile camera scanning harsh, overlit corridors of maximum-security pens, staying put to look unblinkingly at the man dressed in institutional white. The grainy quality of the video stock transferred to film actually accentuates the inquiring vision. It is as if, by blowing up the picture and scrutinizing it for details, director and spectator alike will finally penetrate into the truth.

Licensed To Kill invites the usual cognitive dissonance when beholding those who on screen are humans and off screen are monsters. In any group of seven men, not excepting murderers, some will be more articulate, congenial, and photogenic than others. Some will be poster-boy stereotypes of Neanderthal homophobes, others quite nice fellows, really. At one extreme is a stone-cold sociopath like Donald Aldrich, who looked upon robbing gay men as a smart career move when compared to the risk of knocking over 7-11s. Ditto a low IQ lout like the young Jeffrey Swinford, a punk nightmare with a Mohawk haircut and goatee, unrepentant about his murder of Chris Miller, a former Miss Gay Arkansas, who allegedly hit on Swinford’s best friend. “Just one less problem the world had to mess with,” he mutters.

At the other end of the spectrum is the multiracial multiple personality Jay Johnson, self-deprecating, friendly, and a double murderer. A once-closeted gay man, now HIV positive, he speaks eloquently about his detachment from both races and either sexual preference. Homophobic? No, he explains, carefully, “homophobia” means fear of gays — his attitude was hostility, loathing. Reared on The 700 Club, always tense and ill at ease cruising in the park, he experienced the irony of being “unsuccessful at something you hate” — namely his own sexuality. Mopping his brow with a towel, he admits “to the extent that I was doing it,” he was “disgusted with myself.”

Off camera, but looking the killers straight in the eye, Dong keeps his own emotions well in check. No Mike Wallace, he seeks to draw them out and, like any good interviewer, gets to the Big Question by asking the little ones. How did you do it precisely? Why this man at this time? The sincere interest and non judgmental questions make some of these guys, seasoned bullshit artists though they are, do on camera what apparently has not occurred to them to do before: think about their real motives.

Casting a wider net of indictment, Dong depicts the complicit wraparound of American culture. Images of Pat Robertson, Lou Sheldon, Ralph Reed, and Jerry Falwell float by in ominous slo-mo and fade into the faces of the murders. Cheap shots and over simple analysis perhaps, but the consistency with which biblical authority is invoked to justify the hatred of thy gay neighbor is undeniable. Dong shows a still picture of a man holding up a sign reading “God Said Kill Fags — Lev. 20:13,” a not unreasonable reading of Leviticus: “If a man lies with a man as one lies with a woman, both of them have done what is an abomination. They must be put to death.”

The single-minded focus on the motives of the killers inevitably slights the lives of the victims. Dong compensates with brief, respectful obituaries, still photos and written crawls giving faces and names to the victims, like the pictures which grieving relatives put on tombstones. Of course, the terrible truth is that the victims here — the men with futures and families — are incidental. They could have been anyone, or rather any gay anyone. Corey Burley, a loquacious murderer with an easy smile, is stopped short when Dong asks him about his victim, a Vietnamese immigrant named Thanh Nguyen who came to America to escape the war. “Came to escape the war and got killed by nonsense,” he says ruefully.

The title of Licensed To Kill presumes a sense of entitlement, implying that killers of gay men are not so much cultural pariahs as pure products of America. But if segments of a subculture deem homophobia a permissible, even righteous, bigotry, the law of the land has put the murderers under lock and key and sentenced one to die with a needle in his arm. The film opens and closes with images of violence against gay men and the sounds of hate, culled from the answering machines of Gay/Lesbian alliances, mixed on the soundtrack in an audio collage. Even after Dong’s scrupulous and enlightening inquiry, the source of the venom in the voices still seems beyond understanding. What, one wonders, are they so afraid of? TD.

————————————————————————

THE INTERVIEW

CINEASTE: What was your initial motivation for making this film?

ARTHUR DONG: Licensed To Kill was a long time gestating. I think that my own incident didn’t tell me to make a film. What it did was provoke me into trying to figure out why these crimes happen at all, and just to explore and research it in whatever way I could to try and understand it. A couple of years after the incident in 1977, I re-enrolled into film school. My first film dealt with sexual mores and violence and the interrelationship between the two. I realized that this was a medium that reaches a lot of people all at once; it wasn’t like a painting on a wall where people come in and out and look at it.

When I worked as staff producer for KCET, the PBS affiliate in Los Angeles, I did half-hour documentaries on citizens patrol groups for the gay community in Long Beach and on sting operations that the police were conducting to catch gay bashers. I did it in six weeks, start to finish. TV is quick and dirty, which was fine, but for me it didn’t dig deep into the core of the problem. I didn’t really know I was trying to get at that, but that’s what the dissatisfaction was. I wasn’t getting to the core of the problem.

So in 1995 I was given a Rockefeller fellowship and all it required me to do was to think, to develop, to research, whatever it took for me to come up with ideas. I went down to Texas to sit in on this trial of the murder of Nicholas West and that’s when I met Henry Dunn Jr., the defendant. Here was this young man — very polite and soft spoken and fairly good looking — and at the same time all these witnesses would come up and talk about the evil deeds he had done to them, because he had done other gay bashings before finally killing Nicholas West. I couldn’t reconcile that. I couldn’t see that this was the same person. But it was.

What I saw was this very complicated human being. First of all, what I saw was a human being and I couldn’t deny that. He was no longer this monster. He was no longer the monster that beat me up or attacked me. He was this human being. That’s when the real spark came, that this is what I want to do. This is how I’m going to get to the core of this, at least try to get to the core. And I want to meet other killers, not bashers, because I wanted to go to the extreme, which is murder.

CINEASTE: Unfortunately, you had a pretty good range of people to chose from. How did you narrow down your selection process? When you went into it, were you looking for certain types, like the pretty boy, the redneck, the self-denying gay guy, and so on?

DONG: I was familiar with the prototypes of the gay basher, so in the collection of people I wanted the known prototypes — not to say that these are the only kinds of personalities that commit these kind of crimes, but they were at least the ones that had been studied. We wanted one who was in homosexual panic, we wanted another who was gay himself, who was in self denial, one who did it out of robbery, one who murdered a transsexual — which we did get but finally didn’t use. Someone like Kenneth Jr. French [who murdered four people at random in a restaurant — T.D.] we didn’t expect. That wasn’t a prototype we were looking for. Then there are ones like “Mohawk” [Jeffrey Swinford]. You only had to stage a shot to know that he just didn’t like homosexuals. So, there were some personalities we were after and that’s how we based our selection process. We got a pretty good cross-section of them.

CINEASTE: How many killers did you interview?

DONG: I actually interviewed eleven. We visited ten with a camera crew and one refused us on the spot. We interviewed nine on camera and we ended up using six, plus the Raymond Childs interview in the police department. The one that we didn’t interview on camera, Jim Baines, was from Bangor, Maine. I visited him a couple of times. He actually committed his crime in 1984. But he was too nice and his story was just too positive, almost unreal. That’s the case with fear. He was a kid when he committed the crime and now he’s an adult trying to patch his life together and be a good citizen. He still lives in the same town, everybody knows he committed this crime, he’s ashamed of it, but he’s trying to reestablish his life. He’s made efforts to go to high-school students and speak about his crime and tell them how stupid he was.

For another kind of film it would have been perfect — I mean, what an inspirational ending — but I didn’t want that kind of pat answer to the problem. That may be a part of the solution, but if I had put that in the film as my resolution, viewers would say, “Oh, that’s the answer. We have hope.” And my feeling is one of desperation when we come to this issue because the problem is so bad and so complicated and so modulated that there’s not one easy answer. So I decided not to include him in the film.

CINEASTE: Every documentary seems to have one witness whom the camera loves. In Ken Burn’s Civil War series, it’s Shelby Foote. For me, in Licensed To Kill, it was Jay Johnson, an engaging and intriguing character.

DONG: Jay Johnson was hard to edit because he talked constantly, nonstop, and in tangents, going from one story to the other. People think he’s the expert because he’s in the striped shirt and in a conference room. Then they realize, “Oh my God, he’s a murderer.” The ones that didn’t end up in the film were the ones that didn’t work. The murderer I hated cutting out was the man who murdered a transgender person, because those cases are so common. But it just didn’t work. It broke my heart because I really wanted that kind of case in this film. But I’m ruthless with myself. If it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work. But for me they all worked in terms of screen presence, the way they communicated ideas. Different people have different favorites.

CINEASTE: As it were…

DONG: Maybe that’s not the right word — which ones they find most compelling. I know there are certain moments that I especially find compelling, like the moment that I asked Kenneth Jr. French what he thought about the reaction of the gay and lesbian community to his crime. And he floundered there, he just blanked out for a moment. In fact, he says he lost his train of thought. For the first time in the interview he loses his train of thought and he was very under control.

Or during the interview with William Cross [who stabbed an older man to death — T.D.] When we started the interview, I didn’t realize that he would tell me about being sexually abused as a child and it being linked to his crime. I’m not sure if he felt there was a real link but what I wanted to understand clearly was that moment of rage that he talks about, to really delineate and differentiate the rage that came out of the fear of being hurt by this man and being raped again and losing his masculinity. These are two very different things and it was very important for me to understand which it was, or a combination of those two. During the interview — you don’t see this in the film — I was trying to make him understand what I was saying about the difference, and what you see on screen is his realization. If finally clicks and he realizes the difference: that he wasn’t really afraid of being hurt, that he was afraid of being sodomized again, of being raped.

And the moment with Corey Burley when I asked him if he knew anything about his victim. Obviously, he had never thought about it. Those moments for me just underline why I really love good interviews on camera. Film purists say, “Oh God, another talking-head film.” But for me those are the moments that are golden, that are magic, that you can’t get any where else, even from actors. Well, you might get it from Meryl Streep.

CINEASTE: You’re balancing the personal and the political throughout the film and there are a couple of moments when the viewer can come to one of two conclusions. One is a fairly negative view of American culture, with Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell, and Ralph Reed creating a climate that incites gay bashing. You sort of indict them as being evil guys and in some ways complicit in what these seven killers have done.

DONG: Yeah, I dissolve Jerry Falwell into Jay Johnson’s graduation picture.

CINEASTE: But at the end of the film, although people get murdered, the killers are in jail, one of them is sentenced to death by a rural Texas jury. In a way, that’s a happy ending — everybody you talk to is in jail and punished for their horrendous crimes. For all the grimness, your film could be seen as hopeful.

DONG: I juxtapose that with a collage of very vile telephone calls on answering machines as voice-over at the end. So these men are in jail, yes, but there are countless others out there on the loose. I’m not saying I end this film without any kind of hope. The last statement you really hear is from Corey Burly, where he talks about his wanting to be “bad,” about having “a nitro heart.” He says, “Yeah, I was bad. But where’d that get me? I’m in here. I’m bad but I’m locked up.” You couldn’t script lines like that. It’s so heartfelt. So that’s a glimmer of hope. At least he realizes what a position he’s put himself in and how he’s wasted his life “being bad.” But he says it in such an eloquent way that it’s not syrupy.

The fact that these men have been arrested and convicted is a glimmer of hope — but at the same time I wanted to pull some of that hope away because the problem still exists. That’s why at the end I juxtapose the convictions with the telephone calls. And the last beat of the telephone calls is a guy saying , “FFFFaaaggggottt.” It’s a mix, it’s not easy, and I wanted to end the film uneasily.

CINEASTE: Licensed To Kill doesn’t give the victims of violence much of a voice; your focus throughout is really the killers.

DONG: From the very beginning my concept for the film was to give a forum for these murderers to tell their stories. In fact, in my first few assemblies I hardly had to tell their stories. In fact, in my first few assemblies I hardly had any footage of the murder scenes or the bodies and no photos at all of the victims when they were alive. In that construction, it was entirely the murderers’ story and it was overly sympathetic towards them because there was no reference to the victims as human beings. There was no sense that the crimes really happened because there was no reference to them. That was a real dilemma because I said, “I don’t want to interview the victims’ families, I don’t want to interview survivors, ex-lovers, or partners.” And I didn’t want to interview experts in the field and talk about the victims’ point of view.

So what I did in the early versions was to start putting in footage of the murder scenes and the bodies, which was very difficult for me to do. First of all, I didn’t want be gratuitous and it was a hard thing to balance. Second, I didn’t want to look at it, and in the editing room I’m looking at every single frame of this stuff. But gradually I started putting it in. The first time I put in shots of a dead body was with the shots of Thanh Nguyen in the park in Dallas. That was very difficult. It took me about four hours to put in three shots, because I was thinking about the timing and rhythm as well as getting used to the idea of putting this stuff in. Each shot is two seconds long. Then I started putting in still pictures of the victims alive because their deaths were so violent and vile that I didn’t want those to be the images audiences have of these victims.

CINEASTE: You didn’t put in portraits of their partners or parents, though.

DONG: No I didn’t. That would have interrupted the flow of the film. I had these mini-obituaries — the names, the ages, and the dates they died. There’s actually a balance; sometimes I have a little music, while others are in complete silence. As I got into this rhythm, they served as a counterpoint to the prisoners’ stories. Not so much an indictment of what they did, just a balance so that we don’t forget the act. I let the killers describe the act, what they did, but without showing it. It becomes very abstract.

I think because as viewers we’ve become so desensitized — with the enormous amount of visuals that we get in the mass media, whether fictional or real, of bodies mangled, murdered, and desecrated — that I needed to counter the desensitivity. The images that I have in the film of the murders are not as gruesome as some of the stuff I see on The X-Files or Millennium. But, I think because audiences know that these images are real, that makes it more devastating.

Many viewers have come up to me and said that, of all the images of murders in the film, the most effective one for them was that of the severed finger [of Nicholas West shot nine times — T.D.] because it’s so cryptic, so horrendous. Why would you go so far as to chop off someone’s finger?

So, as a filmmaker, once I got into the rhythm, I said. “Oh, this is what’s happening. I’m doing counterpoint.” Pretty soon they become just images to me — I mean, I never forgot what they represented, but I was able to use them as filmmaking elements.

CINEASTE: People also comment on your decision not to include killers of lesbians; you focus exclusively on men who kill gay men.

DONG: We did try to get a lesbian killer. Statistically speaking, it’s about seven percent, but that’s statistics. There are reasons why that number may be higher but under reported. We contacted seven killers of lesbians and they either said no or just didn’t respond. We’re not really sure why. We were very disappointed. In the end, though, I think it actually helped us — I may be rationalizing — because it became a film about men and male sexuality, and it became much stronger. I think that other film should be made, too. It’s just not this film.

CINEASTE: Licensed To Kill II?

DONG: Licensed To Kill Again or Licensed To Kill Some More. The film I’d really like to make is Licensed To Kill …Canceled.

————————————————————————

Copyright 1997 by Cineaste Publishers, Inc.

Reprinted with permission